By Perry J. Saidman

In the recent opinion Wallace v. Ideavillage Products Corp., the Federal Circuit made even more explicit a trend in recent district court design patent infringement cases to consider both whether the patented and accused designs are “sufficiently distinct” to avoid infringement, and also whether the prior art is closer to the patented design than the accused design, or vice-versa (the 3-way comparison).

Although unpublished, this opinion is the first since the Federal Circuit’s Revision Military case to acknowledge and approve this approach. In fact, the Court in Wallace officially dubbed the approach as the “first stage” and “second stage” of the ordinary observer test.

As reported in a previous edition of this newsletter, the Court some time ago reversed and remanded the district court’s finding of non-infringement in Revision Military based on its finding that the patented and accused designs were “sufficiently distinct” such that one did not need to consider the prior art. On appeal, the Court in Revision reviewed the prior art, and determined that it was in fact relevant to the infringement determination, and remanded to the district court with instructions to consider the prior art. Since then, many district courts appropriately have been paying much closer attention to the prior art.

In Wallace, the Court quoted the district court with approval:

“The ordinary observer test proceeds in two stages. “In some instances, the claimed design and the accused design will be sufficiently distinct that it will be clear without more that the patentee has not met its burden of proving the two designs would appear ‘substantially the same’ to the ordinary observer…” (citing Egyptian Goddess).

“In other instances, when the claimed and accused designs are not plainly dissimilar, resolution of the question whether the ordinary observer would consider the two designs to be substantially the same will benefit from a comparison of the claimed and accused designs with the prior art…” Id.

The Federal Circuit then stated: “The district court applied both stages and determined under both tests that an ordinary observer would not consider Ms. Wallace’s patented design and the Ideavillage design to be substantially the same.”

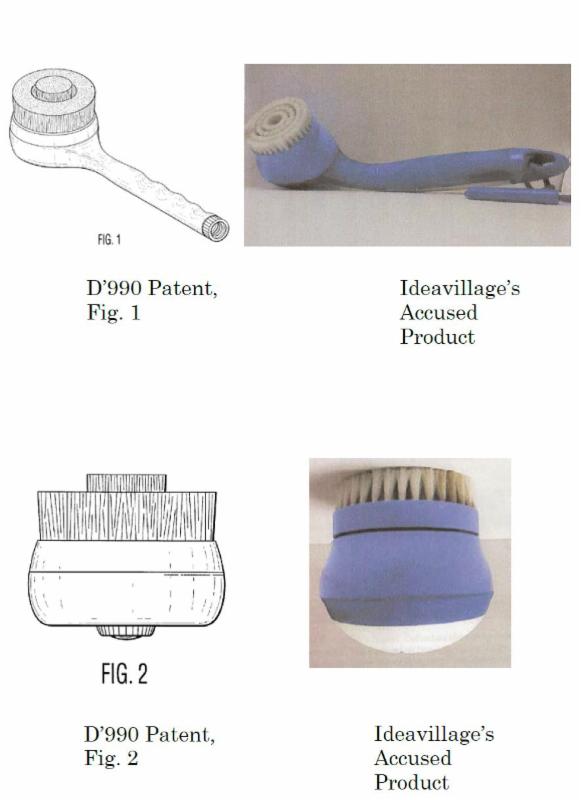

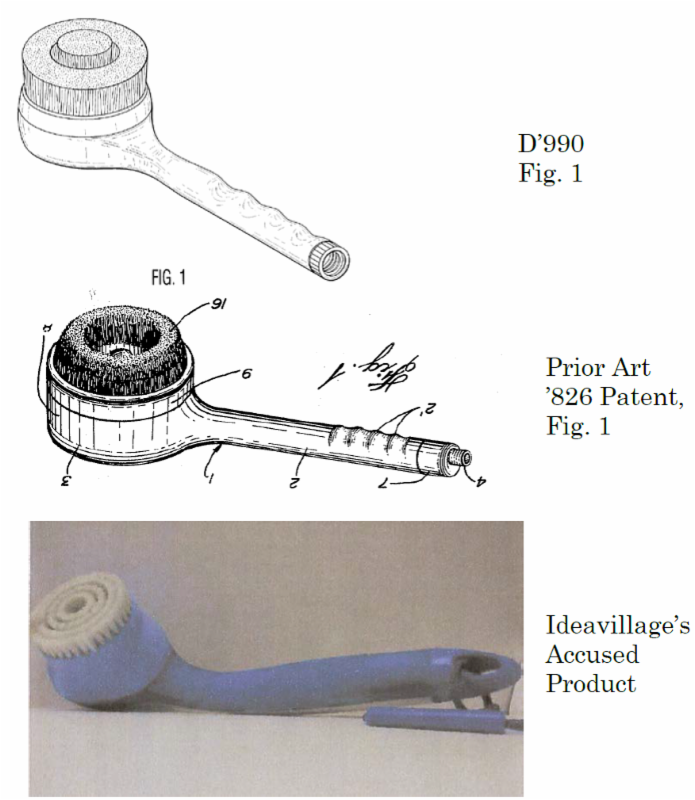

The opinion, written by Judge Newman, helpfully included many images.

After listing similarities and differences, The Federal Circuit magically concluded from the above and other images that the district court properly found that the D’990 patent’s design and the accused product are plainly dissimilar (note: “plainly dissimilar” and “sufficiently distinct” essentially mean the same thing).

Importantly the Court then said:

“In an effort to assume a fair and complete decision on this record,” the district court proceeded to the second stage of the ordinary observer test.

Dist. Ct. Op. at *4. Comparing the claimed design with figures from the prior art, U.S. Patent No. 4,417,826 (the ‘826 Patent), reinforces the district court’s findings under the first stage of the test: (emphasis added).

The Federal Circuit quoted the district court as follows:

“[P]laintiff’s ‘990 patent displays significant similarities with the design of the ‘826 patent. Among other things, each design has a rounded head and a straight handle with “hill and valley” finger grip. Each design has a rounded protrusion on the backside of the rounded head.” Id. at *5

The Court then said that the district court properly concluded that “in light of the similarities between the ‘826 patent and the ‘990 patent, … no reasonable ordinary observer, familiar with the prior art, would be deceived into believing the [Ideavillage] [p]roduct is the same as the design depicted in the ‘990 patent.” Id. at 10.

The Court concluded: “The district court correctly applied the law, that “differences between the claimed and accused designs that might not be noticeable in the abstract can become significant to the hypothetical ordinary observer who is conversant with the prior art.” Egyptian Goddess, 543 F.3d at 678.

The summary judgement of non-infringement was affirmed.

The author has no quibble about the outcome of this case based on the comparisons made with the prior art. However, the author still believes that in the vast majority of cases the “sufficiently distinct” and “plainly dissimilar” determinations are far too subjective to be reliable.

By dictating that the ordinary observer test is to take place in two stages, the Federal Circuit is to be applauded in virtually requiring the prior art to be considered in an infringement analysis. After all, a comparison of the patented and accused designs with the prior art is the only objective evidence of infringement in a vast majority of cases.