Functionality Glass is Full

Infringement Glass is Completely Empty

by Perry Saidman

Earlier this year we reported the very good news that the Federal Circuit had done an excellent job in analyzing functionality in the High Point fuzzy slipper case.

Now the Court has gone even higher than High Point in its recent Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc v Covidien Inc decision, 796 F.3d 1312 ( Fed. Cir. 2015), to the point where there is very little left to instruct district courts on how to properly handle functionality defenses in design patent validity challenges.

Unfortunately, the Court slipped back into the morass of “sufficiently distinct” and “plainly dissimilar” regarding infringement, ignoring the most objective evidence available, namely the prior art.

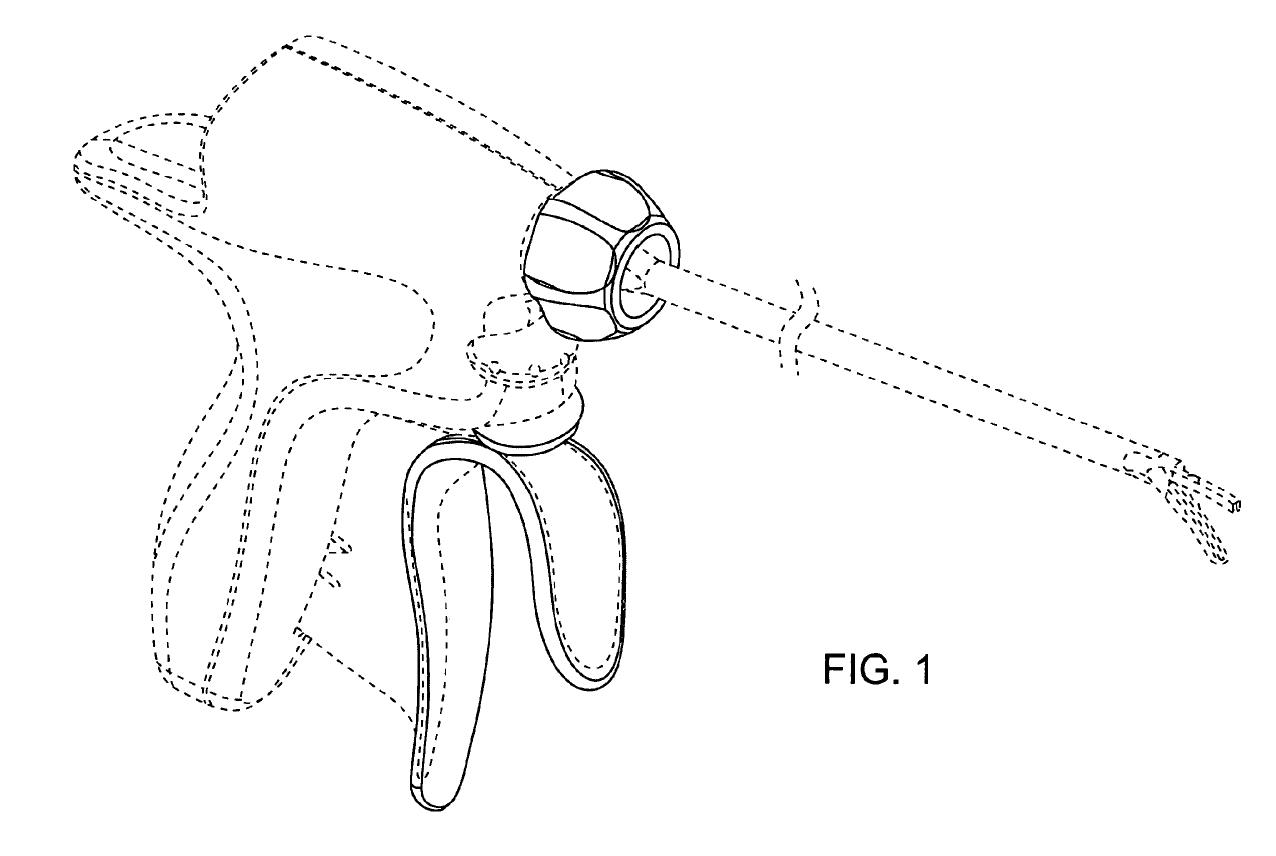

Several ultrasonic surgical device design patents were at issue in Ethicon. Below is shown FIG. 1 from D661,804 which covered the combination of the inverted U-shaped trigger, fluted torque knob, and rounded activation button. Other design patents covered other elements and combinations.

The district court, in granting the infringer’s motion for summary judgement of invalidity and non-infringement, concluded:

A. The claimed designs were all “dictated by function” under the tests identified in PHG v. St. John, and were thus invalid.

B. Because each of the designs of the trigger, torque knob, and button must be “factored out” under Richardson, the design patents had “no scope”, and thus the accused designs did not infringe; and

C. Even if the functional elements were not factored out, there was no infringement since the “highly sophisticated” ordinary observer would find that the patented and accused designs were “plainly dissimilar”.

First, the good news regarding functionality:

1. The Court again recognized that design patents by definition cover articles of manufacture that necessarily include elements that perform a function (Ethicon at 1328).

2. As a corollary to #1, the Court explained that a claimed design was not invalid as functional simply because the “primary features” of the design could perform a function (Id. at 1329).

3. Another corollary is that the overall appearance of the article – the claimed design viewed in its entirety – is the basis of the relevant inquiry, not the individual features (Id.)

4. Significantly, the Court declared that the availability of alternate designs is a dispositive factor in evaluating the legal functionality of a claimed design. (Id. at 1329-30).

5. Helpfully, the Court put Berry Sterling in its place – on a back burner – essentially saying that regardless of the dicta in Berry Sterling (listing a number of trade dress functionality factors (!) to be considered in design patent functionality analysis), the existence of alternate designs is the card a court must lead with. (Id. at 1330).

6. The Court also for the first time clarified that the function to be considered in design patent functionality analysis is the broad function of the design, not the narrow function, saying essentially that the alternate designs don’t need to perform the exact function as the claimed design, only have similar functional capabilities. (Id. at 1331).

7. Interestingly, the Court extended its “design abstraction” test, previously used only with respect to anticipation and obviousness analysis, to functionality analysis under PHG (which was itself a misguided outgrowth of Berry Sterling). The Court criticized the district court in using “too high of a level of abstraction” in describing the functional attributes of the claimed design when it decided whether the alternate designs were the “best design”. (Id.). [Note that the same abstraction logic would apply to functionality analysis during infringement claim construction per the Richardson case, where the Court in fact used too high a level of abstraction in eliminating “functional” elements from the claimed design].

8. As a capper to #7, the Court said that design patent functionality analysis must be performed “at a level of particularity commensurate with the scope of the claims”, rather than focusing on design concepts. (Id. at 1332).

The Court’s functionality analysis is in accord with this author’s 2009 article “Functionality and Design Patent Validity and Infringement“.

Now the bad news regarding infringement.

Well, there’s actually one bit of good news here. The Court vacated the district court’s finding that the design patents covered “nothing”. The district court had come to that conclusion after “factoring out” the “functional” elements from the claimed designs. The Court on appeal clarified both Richardson and Oddz-On saying essentially that any “factoring out” that took place in those cases pertained to design concepts rather than appearance aspects of the particular designs.

As presented in my 2009 article linked above, and as agreed with by the Court, the “factoring out” exercise amounts to nothing more than saying you can’t use a design patent to protect that which you can only protect with a utility patent, i.e., design concepts may only be protected with utility patents, while the specific embodiments of those concepts are the real design patent subject matter, see inter alia, Lee v. Dayton-Hudson, 838 F.2d 1186 (Fed. Cir. 1988).

So much for the bit of good news.

Reaching a rarefied height of subjectivity, the Court affirmed the district court’s finding that the patented and accused designs were “plainly dissimilar” such that consideration of the prior art was not necessary. The Federal Circuit agreed that the two designs were “sufficiently distinct” and did not even discuss the prior art.

I have often stated that to deny the patentee its day in court, before a jury, by granting a motion for summary judgement of non-infringement without even looking at the prior art encourages arbitrary decision-making, and deprives the fact finder of the most probative, objective evidence available: the prior art. Egyptian Goddess modified the Gorham test in requiring that the similarity of the patented and accused designs be viewed “in the context of the prior art”.

Judging infringement without having that context is sheer folly, unless you are comparing a carburetor with a laptop. Of course a person looking at any two designs will be able to see differences – only a reckless infringer would copy the claimed design exactly. So, the challenge in infringement determinations is not to be able to notice similarities and differences between the patented and accused designs; the challenge is comparing the overall designs to the prior art.

Here is the rule of thumb that makes sense: if the patented and accused designs are closer to each other visually than either is to the prior art, infringement is more likely, but if the patented or accused design is closer to the prior art than they are to each other, infringement is less likely.

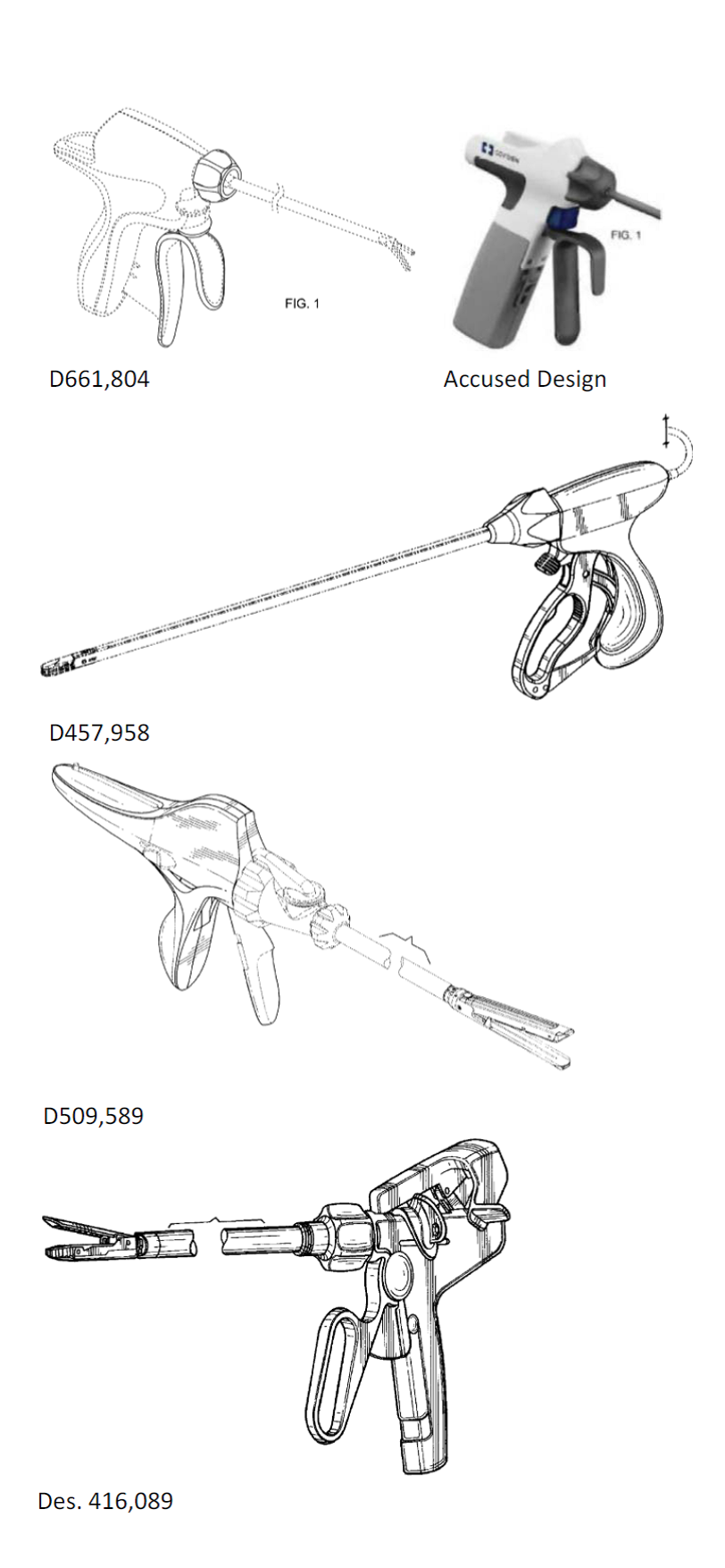

Just for the heck of it, following is the patented design, the accused design and the closest prior art design patents of record:

I’ll let the reader determine which is closer to which. The point here is not who wins and loses, it’s that the comparison between the patented and accused designs cannot take place in a vacuum, subjectively, as did both the district court and the Federal Circuit. In other words, place the best objective evidence – the prior art – in front of a jury, and let them make the fact findings and conclusions as they are supposed to do.