Court Decision Typifies an All Too Common – and Incorrect – Functionality Analysis

Perry J. Saidman

In Tactical Medical Solutions, Inc. v. Dr. Ronald Karl and EMI Emergency Medical International a/k/a Emergency Medical Instruments (ND Ill., June 11, 2019), the court denied EMI’s motion for summary judgment (MSJ) of design patent invalidity based on functionality.

The court’s opinion missed the mark in holding that the issue of functionality in this case needs to be decided by the jury, saying material facts were in dispute.

The author posits that the issue of functionality was clear cut; the claimed design was not functional as a matter of law.

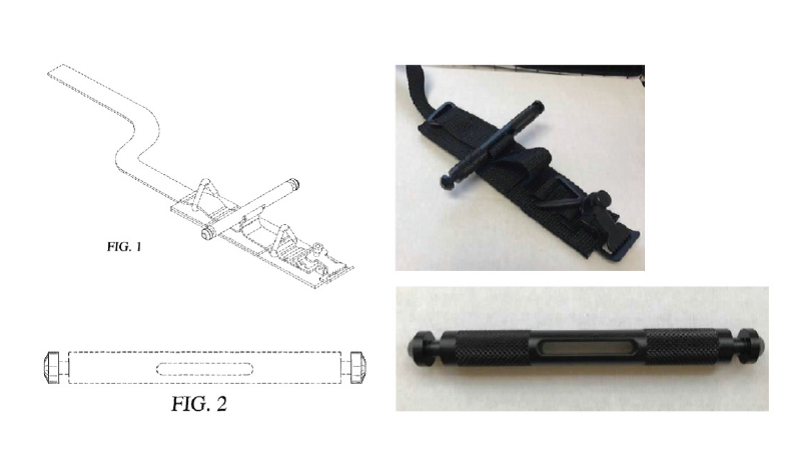

Below is the plaintiff TMS’s U.S. Pat. No. D649,642, next to images of the accused design.

Note that the claimed design is confined to the shape of the beveled ends, shown in solid lines.

The court relied on the Federal Circuit’s 2015 Ethicon decision, which is the go-to case for design patent functionality.

The district court began on the wrong foot in misquoting Ethicon where it said: “The existence of alternative designs is an important but not dispositive factor [in determining functionality].” (Slip. op. at 14).

The Federal Circuit actually said just the opposite: “…the availability of alternative designs [is] an important – if not dispositive – factor in evaluating the legal functionality of a claimed design.” Ethicon at 1329-1330.

In other words, the Federal Circuit elevated the importance of alternative designs by saying it was very likely a dispositive factor, while the district court reduced the importance of alternative designs by saying that it was not dispositive. This led the district court to analyze the discredited Berry Sterling “factors” (which were dicta in that case), such as “whether the protected design is the best design.” One might as well ask why this factor should matter. Does this factor incentivize the patentee to prove its design is less than the best, or to intentionally make an inferior product? Do witnesses need to testify about the excellence or poor aesthetics of a design? Or, worse yet, the excellence or poor utilitarian aspects of a design? Does this make any sense? As this author has previously written, the functionality factors in Berry Sterling are eerily (and improperly) similar to the factors for determining trade dress functionality (perhaps the result of a law clerk’s sloppy research).

Further, the availability of alternative designs is always dispositive of the issue of design patent functionality. The purpose of the functionality doctrine is to prevent the patentee from using a design patent as a utility patent, i.e., using a design patent to monopolize the function embodied by the claimed design. Thus, if there are alternative designs to the one claimed, that perform substantially the same function, it is proof positive that the claimed design is not monopolizing that function, and therefore is not functional as a matter of law. Period. End of analysis.

In other words, the alternative designs test trumps other considerations, as it should.

The district court compounded its shaky analysis when it examined the “functional purpose” of the beveled ends of the design, forgetting that it’s not the purpose or utilitarian aspects that matter, but rather the appearance aspects. As pointed out in Ethicon: “Articles of manufacture necessarily serve a utilitarian purpose, but design patents are directed to ornamental designs of such articles”, Id. at 1328. Stated differently, all products have utilitarian features, but it’s the appearance of those features that are protected by a design patent.

When the district court finally looked at alternative designs, which clearly existed, it discounted them, saying: “…it is not clear [that] those alternative designs would work as well”, echoing another piece of misguided dicta from Berry Sterling. Having concluded that the issue of functionality could go either way, the court left the issue for the jury.

Let’s hope that design patent litigants – and eventually the courts – will someday “get” how the issue of functionality should be properly analyzed, and avoid wasting court resources.